Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: How the Mania Hit Australia

Table of Contents

- How a comic about pizza‑eating sewer heroes became a nationwide craze

- Creators, commerce and the global toy machine

- Why kids loved them — and why adults worried

- Expert views: does cartoon violence change behaviour?

- Schools, parents and the limits of prohibition

- What to do if your child loves the turtles

- Key takeaways

- Frequently asked questions

How a comic about pizza‑eating sewer heroes became a nationwide craze

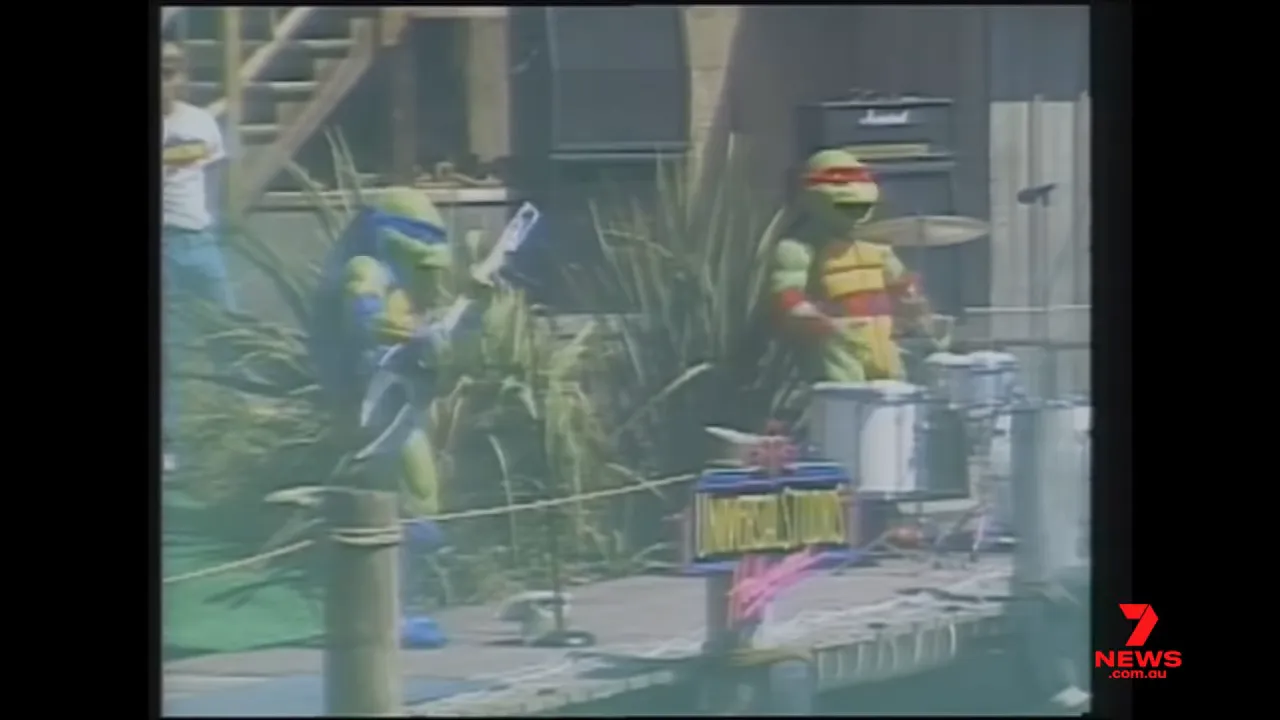

The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles swept through Australia in the late 1980s and early 1990s, turning four comic‑book creations into a merchandising juggernaut. What began as a US indie comic financed with about US$1,200 grew into a cultural phenomenon that pushed $130 million in toys, clothing and movie tickets in Australia alone.

The turtles — Michelangelo, Donatello, Leonardo and Raphael — arrived on TV screens, shop shelves and playgrounds. Their mix of martial arts, slang and pizza made them instantly recognisable to kids, while advertisers and licensees rapidly flooded the market with action figures, apparel and tie‑ins.

Creators, commerce and the global toy machine

Peter Laird and Kevin Eastman created the characters in a newspaper comic strip before TV and film amplified their reach. Toy factories, especially in Asia, struggled to keep up with global demand as retailers stocked hundreds of different Turtle products.

Industry insiders flagged the scale: there were more than 600 targeted products for children aged five to ten, plus records, live shows and celebrity appearances. For many families, the turtles were unavoidable — and lucrative for manufacturers and media companies.

Why kids loved them — and why adults worried

Children responded to clear heroes who won fights, ate pizza and talked like “radical dudes”. For boys especially, the appeal was physical: the turtles fought enemies with of‑the‑moment weapons and performed recognisable moves that were easy to imitate.

But the same traits sparked concern. Some educators and parents worried that repeated exposure to animated violence normalised aggression and encouraged playground mimicry. One deputy principal instituted a blanket ban on turtle toys and talk for younger students to reduce incidents of imitative play.

Expert views: does cartoon violence change behaviour?

Psychologists interviewed at the time argued that visual media have a strong impact on children. Repeated depictions of conflict resolved through fighting, they warned, can embed the idea that violence is a default solution.

“Things that people see tends to have a greater impact than what people hear,” remarked one expert, pointing to the cumulative effect of violent episodes on young viewers.

At the same time, broadcasting regulators reviewed complaints and concluded that, in isolation, the program’s audience response didn’t yet warrant rescheduling or removal. Children themselves often distinguished cartoon death from real‑world harm and said they liked that the “goodies” won.

Schools, parents and the limits of prohibition

Bans and classroom rules were one response, but educators warned that outright prohibition could be impractical. History shows strict bans can push trends underground rather than solve the underlying behaviour.

Many experts recommended using the craze as a teaching moment: discuss conflict resolution, model peaceful behaviour and talk with children about on‑screen actions versus real‑life consequences.

What to do if your child loves the turtles

Parents can keep the toy or TV issue manageable by setting simple boundaries and encouraging conversation. Watch together, ask questions about the scenes that worry you, and suggest alternative ways the characters could solve problems.

- Limit unsupervised viewing of action scenes.

- Encourage role play that emphasises teamwork, not fighting.

- Use toy time to talk about safe play and real‑world problem solving.

Key takeaways

- The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles grew from a $1,200 comic into a multibillion‑dollar global brand, dominating Australian kids’ culture in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

- Commercial success brought widespread merchandising, live events and even music releases aimed at young fans.

- Concerns about cartoon violence led some schools and parents to limit turtle‑themed play, while regulators balanced complaints against audience research.

- Experts suggest discussion and guidance are more effective than outright bans when managing media influence on children.

Frequently asked questions

Why did Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles become so popular with Australian kids?

The characters combined action, humour and a distinct look with simple, repeatable catchphrases and moves. TV exposure, film tie‑ins and an enormous range of toys made them highly visible and desirable to children across Australia.

Were schools really banning turtle toys and games?

Yes. Some schools reported imitation of aggressive behaviour and put temporary bans or restrictions in place to reduce playground incidents and promote peaceful play among younger students.

Did experts agree that the cartoons caused violent behaviour?

Views were mixed. Psychologists warned that repeated visual depictions of violence can influence how children perceive conflict resolution, while broadcasters and other authorities noted that many children understand cartoon violence as fictional.

Is banning a popular cartoon the best solution?

Most experts suggested that banning is rarely effective long term. A better approach is supervised viewing, open discussion about on‑screen actions, and teaching alternative ways to handle conflict.

The information in this article has been adapted from mainstream news sources and video reports published on official channels. Watch the full video here 'Radical dude!': How Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle mania came to Australia | 7NEWS